B-Movie Incantations

Doug Campbell in conversation with Gary Cummiskey

Doug Campbell was born in Edinburgh, Scotland, where he still lives. He is an artist who works primarily in collage. When he was a child he discovered the word ‘surrealist’ in a science fiction novel and then was given a small book of Surrealist paintings. This was the first step in an adventure that continues until this day. He has an ongoing engagement with the international Surrealist movement through correspondence, collective games, and contributions to publications and group shows.

Artist photo credit: Janice Hathaway

When did you become interested in art and when did you start making art? At what point did you become acquainted with surrealism?

I don’t remember ever not being interested in art, in the widest sense, from my first picture books and comics onwards. I drew obsessively as a kid, grew up making and painting models and graduated into making posters for gigs as a teen and an adult. All this in spite of bad experiences at school, being told off for talking back to art teachers and having my work torn up in front of the class. Anything I know about composition, I picked up from Marvel comics, paperback covers and movie posters. It always mattered.

I first encountered the word ‘surrealist’ in a science fiction novel as a kid. I asked my parents what it meant, and was shown a little book of paintings that fascinated me by Alfred Schmeller (1956), part of the Methuen ‘Movements in Modern Art’ series. 24 colour plates, with Magritte, Tanguy, lots of Ernst. I still have it.

What is your technique in making collages? Do you prefer analogue to digital?

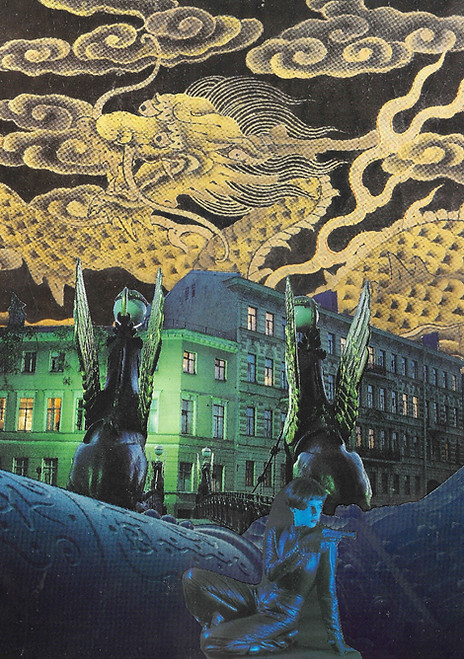

Most of my work is analogue. I buy second-hand books from local charity shops, harvest images that seem to me to have some kind of magic, and combine them using scissors, glue and scalpel. Final assembly of a collage usually takes just an afternoon. I work intuitively, guided by colour, texture, lighting and composition. I imagine the process as something like creating a toy theatre or a doll’s house. I find the constraints imposed by found source material productive. They force me to discover scenes that I wouldn’t have thought of otherwise. Any symbolism is purely unconscious. The title comes last, suggested by the completed picture. I welcome other people’s interpretations of my imagery, though these are very rarely offered. When it happens, it’s like a tarot reading, something to be contemplated.

I have made digital collages occasionally, but it’s an entirely different experience. You can call up any image you can think of from the internet, so that sense of discovery isn’t there. There is the temptation to indulge rather obvious fantasies of one kind or another, or to create didactic cartoon imagery.

You are creating a seemingly ongoing collage novel called The Cabinet of Major Weir, which is online. How did this originate? I assume Ernst’s collage novels were an influence?

I discovered Ernst’s The Hundred Headless Woman in the university library, and was transfixed. I know people love the antique cross-hatched texture of the prints Ernst worked with, but I was thrilled by the dynamic energy they derived from the pulp fiction that they illustrated. Heroes escape, lovers embrace, villains gloat. Action-packed romance at every turn. Here was a narrative language I recognised, but unmoored from its storylines to express totally new mysteries with the same urgent, compelling power. I try to tap into that energy using modern source material.

When I first started making collage, it was a slow, uncertain process. I assembled perhaps half a dozen pieces over a couple of decades. Then, in 2017, I participated in the ‘Archaeology of Hope’, an extended surrealist game instigated by Merl Fluin and Paul Cowdell. It’s a long story, but I committed to creating an entire deck of collaged playing cards over four days and hit the charity shops for sourcebooks. I had previously been inhibited about cutting up books, but here was an inexhaustible supply of modern imagery at throwaway prices. Crucially, the pressure of working to a specific constraint suddenly made everything very easy, and I swiftly completed the deck.

This suggested the idea of adopting the collage novel as a model for a creative game: I committed myself to produce a collage every week, to be shared on the same day like an episode of a TV series. The process quickly became a routine part of my week, and I’ve been doing it ever since. The activity is something I look forward to, perhaps even therapeutic. The completion of a picture delivers the satisfaction of a solved puzzle, and I’m usually surprised by the final image. Repetition makes it easier to get into the creative headspace. It has been suggested to me that this repeated practice could be seen as a form of ritual magic. I hadn’t ever thought of it that way, but then all I would ever want from magic is to see into other worlds and dimensions, so there’s that.

The series is divided into fifty-episode ‘novels’. Fifty is an arbitrary number, but I find each novel still feels like a new start under a new title. There is no through-plot in the series beyond whatever is happening in my unconscious, but certain archetypal figures and environments seem to recur. In retrospect, I can sometimes see the impact of events in my day-to-day life. Major Weir himself is a legend of my home town, a historic figure executed for witchcraft. He is supposed to haunt the streets at night, in a coach drawn by headless horse, and driven by a headless horseman.

You seem to have a great interest in horror movies – when did this start?

I encountered the imagery of horror movies long before the films themselves, through pop culture things like Scooby-Doo cartoons, Aurora ‘Glow in the Dark’ models, Topps bubble gum cards and so on. I was a sixties monster kid, and I loved it all. The films themselves were shown rarely and late at night, so it was a very long process of discovery. In the era before digital media, these were holy relics, dead sea scrolls. Finally getting to see a revival of the original King Kong in our local Deco picture palace was a religious experience. Discovering films of this kind has never lost its magic, and I have an extensive library of the works of Jean Rollin, Jess Franco, Paul Naschy and many others. Conventional art house cinema often seems timid by comparison, though I love the films of Fellini, Ken Russell, and David Lynch, along with contemporary directors like Peter Strickland and Bertrand Mandico and many others who sit outside of genres.

Of course, horror contains multiple sub-genres, and for me it is the gothic, fairy tale aspect that appeals. It’s a world in which the irrational rules, and imagination has free rein. I have no interest in grimly realistic portrayals of serial killers. That’s just the daily news, everyday misogyny and abuse, usually served up with the message that we need trigger-happy rogue cops to save us all.

I believe you also have an admiration for HP Lovecraft. Could you tell us more about that?

Last year, I was at the biannual Necronomicon fan convention in Lovecraft’s home town of Providence. I found myself at Lovecraft’s graveside explaining to a couple of strangers how my dad had introduced me to his stories when I was ten, and how great it had been to encounter a writer even more neurotic than I was. Telling the story there and then was a strange, emotional moment. I’d never really put it all together before. I was a very anxious, fearful kid, and HPL really helped me come to terms with the monsters under my bed. I think it’s significant that much of Lovecraft’s imagery and plotting came directly out of his dreams. That gives them a tremendous power.

Of course, as everyone knows, Lovecraft was an awful racist, and it’s important to face that honestly where it comes out in his writing. However, I really don’t think his racism is the central point of his work, nor do I think that’s what draws people to it. For me, it is to do with feeling an outsider in a largely incomprehensible and indifferent world, where even your own identity may be in question. All sorts of people can relate to that, and I think the diversity of an event like Necronomicon tends to bear that out.

What is your opinion of the situation of contemporary surrealism in general, and of British surrealism in particular?

I think there are an awful lot of misconceptions about what surrealism actually is, but despite all that, there are still lots of surrealists around the world working with the ideas and methods, and developing them in ways that are interesting. I think the idea of multiple ‘surrealisms’ is useful here. These groups and individuals are not homogeneous and certainly don’t always agree with each other. For example, surrealism includes both anarchists and trotskyists, militant atheists and pagan witches and so on.

We seem to be living through a moment in which surrealism and surrealists are academically respectable, with major retrospective exhibitions and a lot of books coming out. These phenomena are not in themselves surrealist, and this will pass, but I’m sure more people will be drawn into surrealist activities as a result.

In terms of Britain, the Leeds Surrealist group have been active since the 1990s. Franklin Rosemont put me in touch with the group, I got to know them and participated in a number of their games and activities. Through this, I learned a lot about what surrealism is and how it is practised, and have met many other surrealists. We’ve certainly had our differences, but I think their surrealist practice is exemplary, and their journals are well worth picking up.

There is a long running network of surrealists in Wales, documented in John Richardson’s regular pamphlet ‘Once Upon a Tomorrow/Un Tro Yfory’ and a couple of lavish books by Jean Bonnin. More recently, the Surrealerpool group has emerged in Liverpool and have put out a number of issues of their beautiful magazine ‘Patastrophe. In Scotland, there is now an Edinburgh feminist surrealist group ‘The Debutante’, who produce a fine critical and theoretical magazine of that title. Just last year, a new group in Lancaster produced a fanzine . The line continues, and beyond these groups there are individual practitioners, writers and academics too numerous to mention.

The French poet Lucien Suel, in an interview, once said something to the effect that was a direct line from Dadaism through to near-contemporary movements, such as Situationism, Pop Art, Fluxus and Punk, whereas surrealism was a sort of deviation. What is your opinion of this?

You can absolutely draw lines between these movements, though I don’t think it’s a linear progression. Punk was massively important to me, and I came to the situationists through that, though ultimately came to feel that what I valued in situationist writings was already there in the surrealists. I think perhaps the distinction is that surrealism defined itself in terms of a genealogy running all the way back to roots in primordial myth, whereas the other tendencies were very much about the new, and the modern industrial era.

Jeff Keen was a British film maker, artist and poet who was tremendously influenced by surrealism, but also by pop and outsider art. He is regarded, quite rightly, as one of the top counterculture figures from the 1960s-1970s, yet he is still relatively unknown. What is your opinion of his work?

I’m a huge fan. I first encountered his work on UK TV in the 1980s, a documentary including a generous selection of clips and complete films. My recollection is that it was late night, after the pub. I was absolutely awestruck. The richly layered images of the earlier films, and the futuristic blasts of animated scribbles and collage that followed. Much of the experimental film around back then was slow, minimal, mannered, and often more than a little boring. Keen’s work was nothing like that. A blazing, unstoppable creative energy. Short, intense glimpses of a world buzzing with imagination, colour and humour, often very black humour. Imagery from science fiction and horror, pinups and comics. My kind of stuff. I instantly fell in love with it all.

Unfortunately, pre-internet, I could find no way to follow up on this experience, even with access to a university library. I just had a name, and this incandescent, tantalising memory. It was more than a decade before I could start to put the pieces together. The massive Jeff Keen BFI box set in 2000 was a revelation. Looking back, I can see parallels with New York underground filmmakers like Jack Smith and Ira Cohen who were his contemporaries, and I believe he was every bit their equal and then some. He was producing this magical work out of junk harvested from his immediate environment and working with family and friends. Similar to what was happening over the Atlantic in that way, but distinctively English, coming out of Keen’s home town of Brighton and the pop culture of his place and time. In 2023, I was very fortunate to be able to attend the GAZENTENARY celebration of Keen’s centenary in Brighton, see his film projected, and meet with some of his circle, including his daughter Stella Star, now the custodian of his archive. I acquired an original Jeff Keen drawing, which will always have a place of honour in my home. An inspiration.

What is the contemporary arts scene like in Scotland?

I’m not really a part of it, except as a punter. I didn’t go to art school, and I don’t have a gallery or an agent. My activities are fairly solitary. I’ve had work exhibited in Egypt, France and the US, but never in my own town and always by surrealist groups. Scotland is a small country, but there seems to be quite a lot going on, particularly in performance. I think there’s been a sharp increase in activity since the Covid lockdown. People seem much more keen to get out there and do things!

A couple of us had a conversation on Facebook a short while back about ‘recognition’ – what constitutes ‘recognition’ and when an artist is referred to as being recognised, from whence that ‘recognition’ is coming – and does it have any validly.

I saw a presentation by the curators of the recent Tate ‘Surrealism Beyond Borders’ show, which was revealing in terms of how this all works. For that exhibition, they weren’t able to consider anything that hadn’t been exhibited before, and had arrived at an effective cut-off date of about 1980. They were queried about the latter, but didn’t seem to have an answer, though it is a truism that artists are often only ’recognised’ after they’re dead. One thinks of predators that can only see things that are moving. Perhaps curators can only see things after they have stopped.

I think there’s a kind of institutional ecology involving art dealers and academics and their agendas that would take a team of anthropologists to analyse properly. In my experience, individual dealers and academics genuinely love the work that moves them, but that’s not how the business works and it’s not how the universities work. In practical terms, I think most people can recognise the marvellous when they see it, and that’s actually what matters.

Are you working on any projects at the moment, despite The Cabinet of Major Weir?

I have vague intentions of putting out book of my work, but when it comes down to it, creating new collages always seems more appealing than wrestling with self publishing!

I’m part of La Sirena, an international group of surrealists who have been meeting online since lockdown to play surrealist games, documented on our website. We’ve participated in surrealist events in Cairo, Alabama and at the Maison Breton in Saint Cirque LaPopie and have a few more projects in development. I find travelling to meet and collaborate with surrealists in other parts of the world incredibly rewarding. If anyone out there has an event or a show, I’d love to visit - just get in touch. Surrealism is international or it is nothing.

Apart from that, I’m part of SPG One, a ‘post-punk space rock’ combo playing local pubs and venues. As vocalist, I have been described as providing “b-movie incantations”, something that pleased me very much!

Some exhibitions in which Doug Campbell’s work has appeared

Revelación profana, Fundación Eugenio Granell, Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 2005

The Archaeology of Hope, Shanklin, Isle of Wight, UK, 2017

Surrealism in the Suburbs of Lisbon, Via Aurea Art Gallery, Quinto du Conde, Portugal, 2017

Little Shop of Magic II, The Potteries, Stoke, UK, 2018

International Exhibition of Surrealism, Cairo, Egypt, 2022

Fresh Dirt ‒ Echoes of Contemporary Surrealism, Birmingham, USA 2024

Echoes Surrealistes Contemporains, Maison Andre Breton, Saint-Cirq-Lapopie, France, 2024

Here are some of his artworks:

Irma Vep in the Shadow of the Great Invisibles 2025

.jpeg)

One Third of Human History is Sleep 2025

.jpeg)

Some Knowledge May Be Earned But Some Must Be Stolen 2021

.jpeg)

The Folklorist and Her Prey 2025

.jpeg)

The Good Ship Venus 2021